Ramadan is a month of fasting and feasting. More pious Muslims will say that feasting defies the purpose of the month, that really it is a month for worship only. But for me feasting is integral to Ramadan. It puts our plentiful food into stark contrast with our daytime deprivation, making us even more grateful for the gift that awaits at iftar, food we usually take for granted. It is also a social exercise where the family is brought together to bond over a meal, everyday for 30 days, at a time in our history where work schedules keep us from meeting. It is a ritual whereby all Muslims eat at exactly the same time, a large scale breaking of bread with the power to unite communities and heal wounds brought about by political conflict and war.

Ramadan in Libya revolves around worship and family, so is mostly limited to the mosque and the home. For Libyan women it is food-centric, with the kitchen being their domain for most of the day. For Libyan men it is prayer-centric, with the mosque being their domain for most of the evening. Like most things in Libya, the activities relating to the month are very humble and simple. These are lazy days when day and night simply switch places, daylight hours being more about hibernation than abstention! Daytime is spent at home mostly sleeping and sheltering from the heat of the summer sun. At night the city comes to life; walking along the seafront Corniche (promenade), shopping for Eid clothes or grabbing a snack and chat with friends at a cafe.

Ramadan traditions haven’t changed much over the last century in Tripoli, but three things have faded into a distant memory, soon to be lost forever.

The Iftar Cannon مدفع الإفطار:

The Moors’ great fast of Ramadan is nearly finished; it has been dreadful to them on account of the violent heat of this time of year. The batteries of the castle are fired at the beginning and termination of this fast, and the flags hoisted on all the mosques and forts, the signal for which is one large cannon fired from the Bashaw’s castles. July 29, 1783

Excerpt from “Narrative of a Ten Years’ Residence at Tripoli in Africa, by Miss Tully”

I have never heard the actual cannon fire but it still sits in its place atop of the Saraya. Prior to the February uprising, a virtual canon would shoot on our single Libyan National TV channel before the Maghreb call for prayer. Nowadays with our new found “freedom of speech” (really?!) there are more than a dozen Libyan satellite channels, each taking refuge in a country or city that supports their agenda. I don’t know if they sound the cannon before adan – I haven’t watched any of them because the power is usually cut off – a new Ramadan tradition – abstaining from electricity! So this year I’ve been relying only on the adan of the local mosque.

The Musaharti المسحراتي:

A guard is appointed merely for the purpose of passing through every part of the city at dawn of day, which is the hour the Moors announce their adan, first prayers. This guard warns people in time, to make a hot meal before sun-rise, that they may be enabled to wait for food until sun-set. The people are summoned by a most uncouth noise made by this guard, who carries with him a tin vessel or box, with pieces of loose iron in it. July 29 1783

Excerpt from “Narrative of a Ten Years’ Residence at Tripoli in Africa, by Miss Tully”

Back in the day when Tripoli was confined to the walls of the old city, the Musaharati would beat on his drum or shake a tin rattle, and chant encouraging city dwellers to wake up for suhoor before the Fajr prayers. With Tripoli now sprawling over an area many times its original size, and very few families still living in the Medina, the Musaharati has disappeared. Nowadays people are up from dusk till dawn so the Musharati would have no one to rouse from their slumber anyway! It might be a good idea to give the Musharati a new job of waking people up to go to work in the morning instead!

The Musaharati‘s chant:

سهر الليل يا سهر الليل

داير البركه داير الخيــر

نوضوا تسحروا يا مسلمين

كل عام وأنتم بخيــــــــر

يا نايم وحّد الدايم .. يا غافي وحد الله

يا نايم وحّد مولاك اللي خلقك ما ينساك

قوموا لسحوركم .. جى رمضان يزوركم

Roughly translated:

Up all night, up all night, doing good, doing right

Rise for Suhoor all Muslims

Best wishes for a happy year

Oh sleepy souls remember the Immortal … oh sleepy souls remember the Lord

Oh Sleepy souls remember your Lord, your Maker does not forget you

Rise for suhoor as Ramadan comes to visit you

Kaak Al-Eid كعك العيد:

رمضان سهول وصعوب وسلالات القلوب

Ramadan is first easy, then difficult and finally it strains the heart!

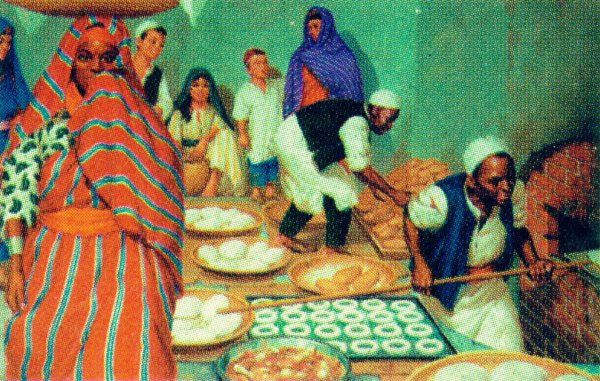

Libyans like to approach Ramadan by splitting it into three manageable parts: as the saying goes the first ten days are easy, the second are more difficult and the third will strain your heart! Traditionally, the third part of Ramadan is focused on preparing for Eid. Huge trays of Ka’ak (ring shaped cookies) and other sweets would be made by the women of the family, gathering to gossip through the night, while the boys take these plentiful trays to the local oven (bakery). Each tray would be marked with a symbol or name (using nail polish – what else!). Iftar becomes all but a forgotten meal, where the feasts of the first week dwindles into a bowl of soup and bread, and if your are lucky, some leftovers from the night before! These days, every family has a kitchen oven, and most families buy Eid sweets from a patisserie or from “at home” bakers who bake to order via Facebook or Instagram!

Libya is in a troublesome state that has left us nostalgic, longing for a time when life was simple and predictable. During this holy month of forgiveness maybe we can find it in ourselves to sit down and start a dialogue over a heart warming meal.

*Note: “The Night Vigil” is the featured image on the left. It is an oil painting by Libyan artist Abdelrezzak Al Riyani (2010).

So nice to read about old Libyan traditions. When I worked in Istanbul I was scared out of my wits the first time the drummer came around pre-dawn. And kind of irritated that at the end of the month I had to tip him for disturbing me every night … Great illustrations too!

I can only imagine being woken by that beating drum, especially when you don’t actually need to get up at that hour! It’s nice to hear from someone who has actually experienced it. Thanks Kate 🙂